One system to emulate them all

A few days ago, I had a heated debate with a friend. It all began after reading the news of the upcoming release of a Berserk inspired game. He argued that there is no element in Berserk that makes it unable to be played with D&D...

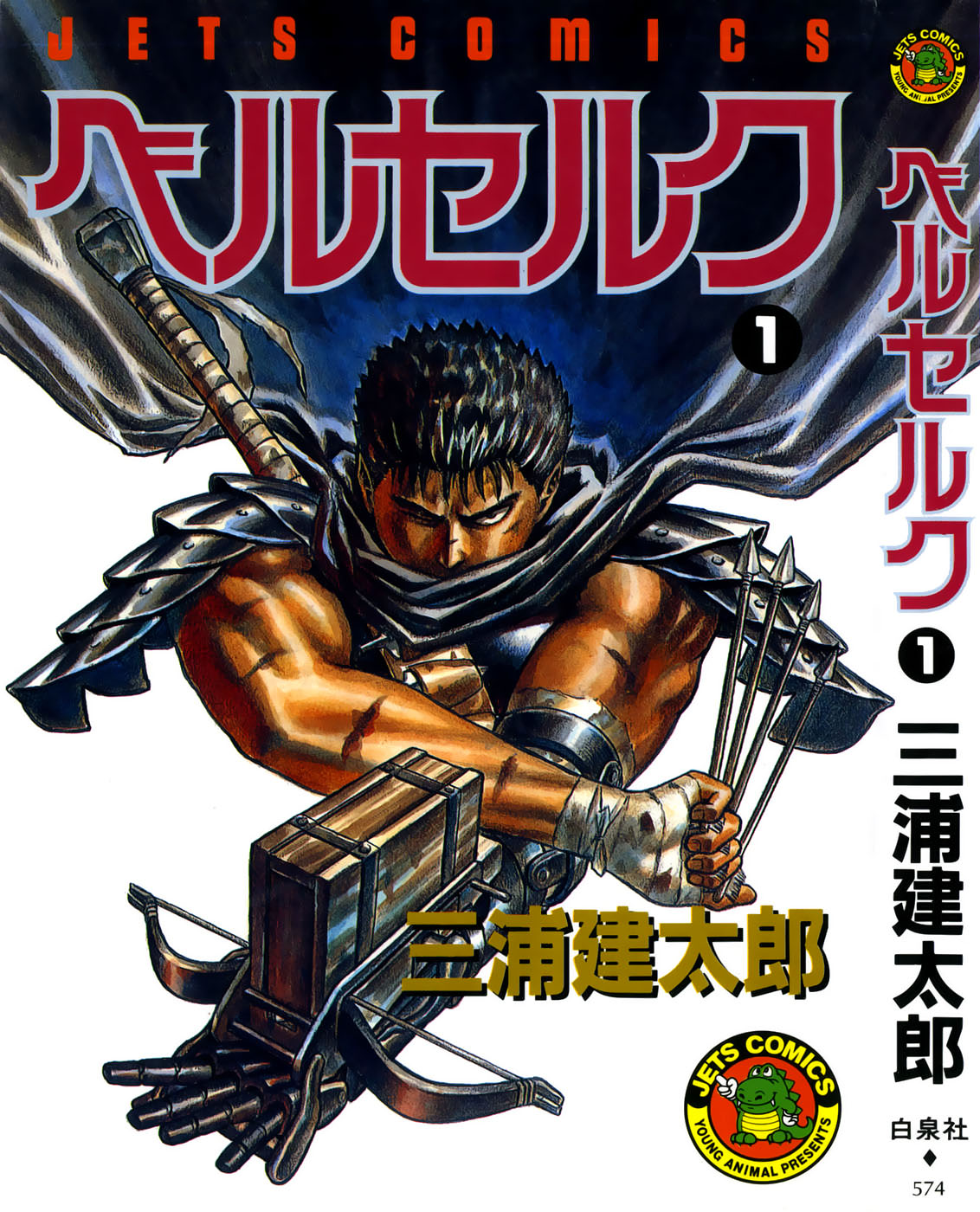

A few days ago, I had (another) heated debate with a friend. It all began after reading the news of the upcoming release of a game inspired by the manga Berserk (Valraven, for those curious about it).

The key of his argument was that there is no element in Berserk that renders it inherently incompatible for its transmutation into the TTRPG hobby through D&D (as it may have happened with other games). We’d already had similar arguments before, but about other IPs, such as Elder Ring or Diablo II.

To avoid being unfair to my friend's uncouth argument, I do want to add that it wasn’t just about using D&D to play everything, but also to have the GM take upon his shoulders the experience of Berserk, Elden Ring, Tolkien, etc., and saving time instead of learning YET ANOTHER set of rules.

I don’t want to reignite such a trite topic, but I do want to focus on an aspect that came up when we were going over the details that should be present in a, for example, Berserk game:

- Is it a game about managing a mercenary group?

- Is it a game about Guts’ and Griffith’s conflict?

- Is it a game about overcoming traumas and unlearning internalized violence?

- Would it be imperative for this game to have only one main character joined by a group of allies?

Why don’t we ask the same question regarding a better known fictional world, let’s say Tolkien and the Middle Earth? What’s the essence of that world that we wish to channel through a game?

- Is it the Middle Earth map, with its races, cultures and its canonical history?

- Is it the theme of a magical and heroic world falling inescapably towards the mundane?

- Is it the story of the fight of Good against Evil, in which the unimportant and menial are destined to turn the tide?

- Is it the story of destroying an object of power, instead of trying to use it “for the cause of Good”?

- Attempting to be even more specific: would it be a game to emulate Frodo’s or Gandalf’s quest? Or the quest of both as part of the Fellowship of the Ring?

The list could go on, and one could probably find good arguments for each proposal. The key is that each answer gives birth to a different kind of game:

If Middle Earth is a map, a list of towns and a canon story, then a game like MERP makes sense (you can read about my experience with MERP here, although in Spanish). If it’s about the story of the Fellowship of the Ring, the game will try to replicate a similar journey, even if the setting can be slightly different. If the game revolves around the loss of magic and heroism, then maybe it should contain fatalistic rules or some attempt to replicate said decadence, or magic should be out of reach for the PCs.

The debate could go on, but what I’d like to establish is that each reading can distill a different “essence” from an IP, or, to be more accurate, that each reader builds a generative structuralist proposal of what they read, given their personal ranking of the text components: one will see the journeys and nature; another one, the fight between Good and Evil; a third one a story about power and corruption, etc. Each proposal is a theory of the key elements of a narration, which would enable the generation of a new one with a similar structure.

Each “theory” about a text can enable the construction of a different system to translate it into ttrpg form. Disregarding the issue of games not being a good tool to emulate other artistic forms (again, you can read another piece about this, by me, but in Spanish), several games could claim to have been inspired by Buffy, for example, and maybe all of them are effectively based on the “text” (the series). Let’s stick to Buffy: this has been the case with Urban Shadows, Monsterhearts, Monster of the Week, Buffy’s official game, etc.

My proposal would explain, partially at least, the internal debates within the fandoms regarding the products inspired by the object of their devotion: each reading is extremely personal and has deep emotional roots. Thus, every reader will have a hard time accepting other possible interpretations as valid.

Some questions that may arise:

Does this multiplicity of interpretations enable the production of 300 games about the Tolkien-verse? We can’t control how prolific the production will be, except for ecological concerns. Somehow, no fiction is ever truly “exhausted” by a single interpretation, and the fact that people keep exploring its possibilities is a good sign of productivity.

Is every proposal equally valid? That is to say: is every interpretation and transformation within a Tolkienian rule system equally valid? No, not at all. Perhaps the reasoning behind why a game is better suited than another one is quite debatable and not at all a binary matter, but an object of criticism as a discipline (as understood by Barthes). However, there definitively are readings and interpretations better founded than others.

What I propose is that no design proposal will ever totally exhaust the fictional genre (or fictional source) that it intends to generate. There will never be a D&D iteration that will forever foreclose the rpg passion for reinventing the dungeoneering fantasy genre over and over again. Besides the already exhibited arguments, there is also the fact that designing is a historical discipline.

In order to conclude, let’s go back to the stance of “play it with D&D”. I said that I wasn’t going to delve into that, but let’s give it a shot: a rule system produces an effect, a certain type of story. A system, however, is not just what’s contained within a set of rules, but it’s also the whole series of procedures adopted by the group: some explicit, others implicit; some idiosyncratic, others imported from previous games or experiences.

Taking into account that learning and getting used to a new set of rules is not without cost (because it entails an effort), it makes sense that somebody would prefer to depend on the unwritten part of the system: what the GM channels. The effort that would imply to learn another game (reading 300 pages of a handbook) could be redirected to developing some tables, subsystems or specific rules to make D&D a little bit more Tolkienlike, or more like Game of Thrones, or more like Berserk. That’s why OSR rejects distancing itself from D&D, but can spend days discussing new initiative rules, how to rewrite hit points, or what to do with the attack and damage rolls.

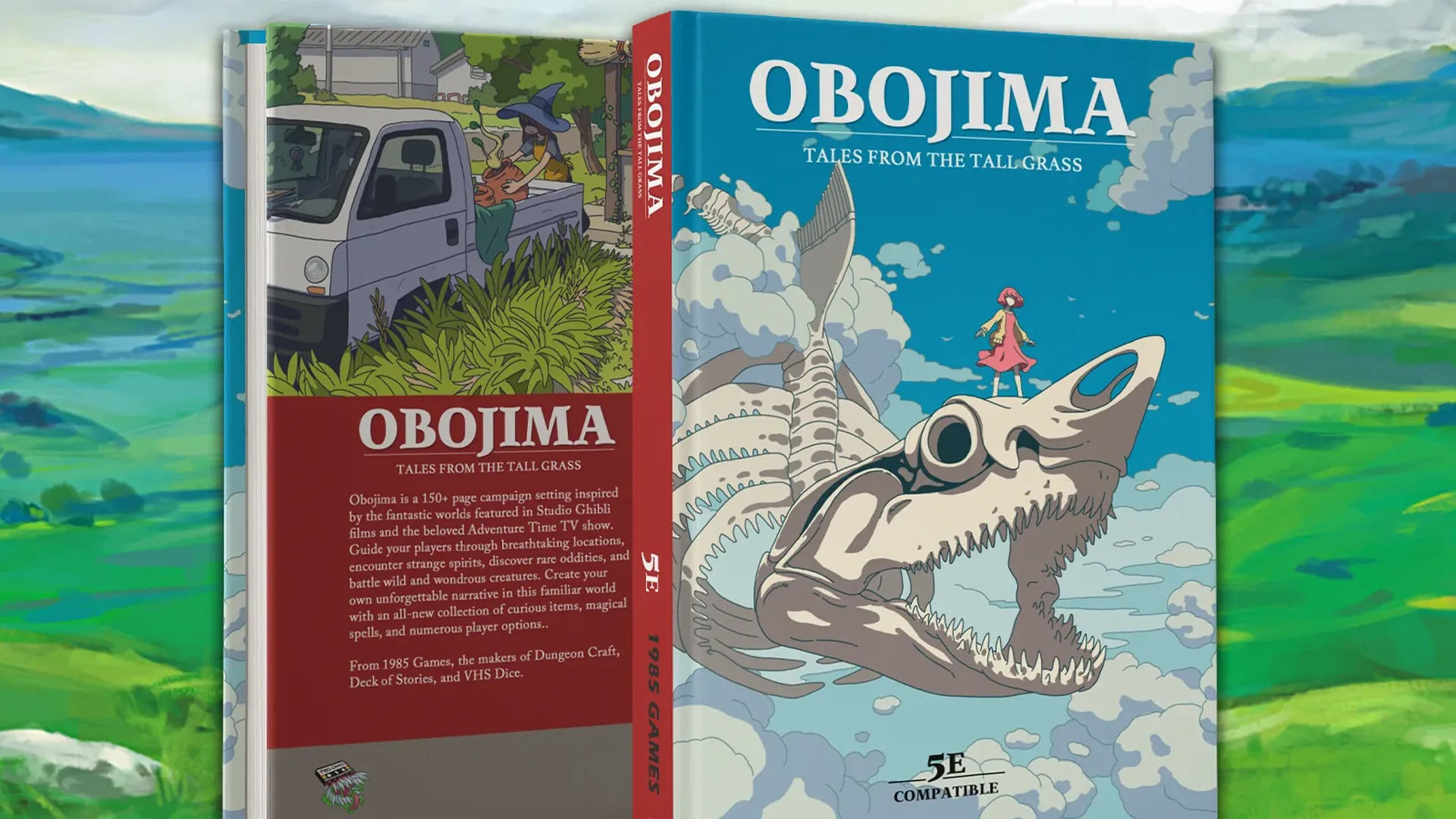

And even though, I admit, it’s easier to modify a common base than reinventing it for every game, this theoretical universality blinds the user to the more than evident effects of the D&D system framework. Some time ago, there was some controversy (another one) about this topic: someone tried to publish a setting or game inspired by the aesthetic of Studio Ghibli films, just to run into a strong rejection from the TTRPG community. D&D is not a game about forming or defending a community, finding a home, or deescalating conflicts and finding ways to coexist. Its rules encourage a certain way of structuring adventures (characters without strong bonds to a community, with power that comes from themselves), accumulating power (obtaining treasure, gaining levels and getting stronger as an individual), and solving conflicts in most cases (combat and a periphery of tactics to avoid it or be better prepared to face it).

That means that when we modify D&D to adapt its style a bit, what we will actually be doing is playing D&D with a little bit of Ghibli/Elden Ring/Berserk/etc. flavour, which isn’t wrong per se, but it can trick some folks and frustrate others who may be looking for something very specific that the game won’t be offering them.

I don’t know if I can offer any strong conclusion that settles the issue for good, but I’ll repeat my main arguments: choosing or designing a game is not an act without consequences and, simultaneously, no specific game can foreclose the creative exploration of designing and playing, which is not only a long-standing tradition, but also infinite in its possibilities and branches. Or, to quote Mallarmé, “A throw of the dice will never abolish chance”.